The North Fairfield Parish

Before Easton existed, there was the North Fairfield Presbyterian Society, which was founded in 1762 to serve the needs of the outliers who settled in this once northernmost region of Fairfield. Established on October 14, the North Fairfield Parish was a religious and governing body. The church building was a place of worship and a civic center where town meetings were held. The parish taxed its members; in return, it provided for roads and schools.

Samuel Staples, a wealthy local landowner who served as the parish’s first clerk, gave the land for the meeting house and donated the first church bell. The original 18th-century building was a primitive structure just north of Center Road. It was a plain timber-framed and shingled building, measuring 47 feet long and 35 feet wide, and it was located almost precisely where the current structure stands.

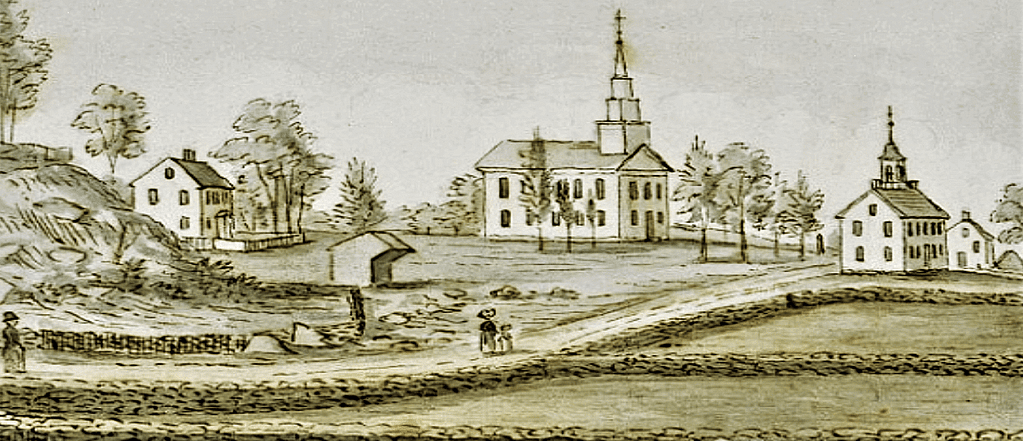

Set prominently on a hill, its exterior simplicity was matched by an interior devoid of decorations, statues, or stained glass. Large windows on the ground floor and gallery levels made the most of natural light. Its earliest appearance may be preserved in the Harriet Jennings embroidery sampler dated September 8, 1830, which shows the two-story structure surrounded by trees.

Fairfield Museum and History Center.

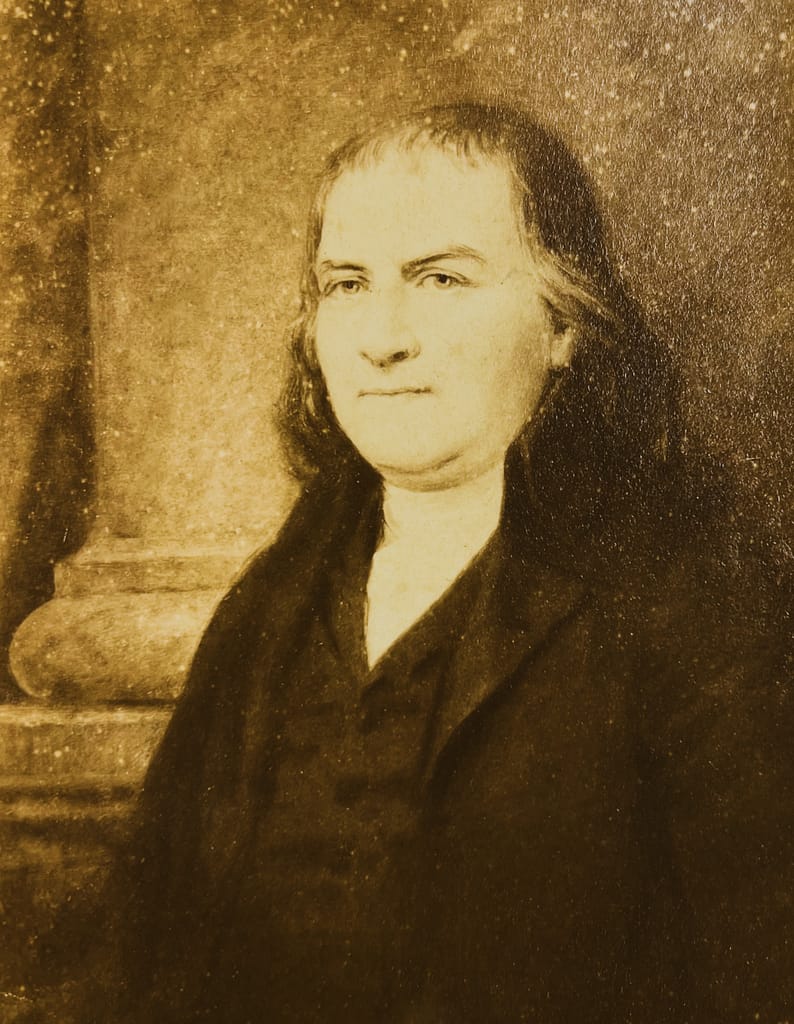

James Johnson, a graduate of Yale in 1760, took the post as the church’s first minister on December 14, 1763. He held the position for 48 years, ushering the congregation through the Revolutionary War and the birth and early development of our nation.

So, what was church like for the North Fairfield Parish in the 18th century?

The Congregationalists were rooted in Puritan beliefs, emphasizing local church autonomy and the authority of the Bible. The services centered on scripture, and included a lengthy sermon, sometimes 1 to 2 hours long. Psalm singing was common, but without instruments. There were no hymns or choirs as we think of them today. Church attire was conservative, modest, and closely tied to social class, gender, and Puritan cultural values—people dressed in their “Sunday best,” but not for fashion.

As Congregationalists, the North Fairfield parishioners also believed that the government should align with God’s will, a crucial notion as Connecticut’s religious landscape was deeply affected by the Great Awakening in the 1730s and 40’s. During this time, a style of revival preaching began to take shape, emphasizing a personal and emotional experience of God that rejected predestination. Adherent ministers were referred to as “New Lights” as opposed to the “Old Lights” who preferred a more traditional and reasoned approach to religious education. “New Lights” preached sermons that used various techniques to inspire religious conversions and spiritual renewal in listeners. This emotionalism is thought to be one of the many factors that helped pave the way for the Revolution and inspired the American people to fight for religious liberty and just governance.

While none of Reverend Johnson’s sermons survive, he attended Yale at a time when these ideas were heavily influential at the university. His library inventory and a few surviving volumes indicate that he owned an extensive assortment of theological commentaries and sermons, including several works by evangelical and “New Lights” ministers, such as Benjamin Trumbull and Jonathan Edwards. Their works in his collection suggest that these ideas informed his approach to ministry. Significantly, Johnson’s library also contained the poetic volumes of Joel Barlow and the pro-militia patriotic sermons of John Carmichael. It seems likely that Johnson expressed not just a fervent call for redemption and salvation from his North Fairfield pulpit, but also the patriotic defense of the new nation.

The published sermon of Reverend John Carmichael titled “A Self-Defensive War Lawful,” was preached to the militia company of Captain Ross in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on June 4, 1775. Reverend Johnson held a copy in his personal library.

Faith in a New Nation

In 1787, the neighboring Norfield and North Fairfield Parishes ceded from Fairfield and joined to become the town of Weston. Samuel Staples, long concerned with providing higher education for poor students, founded an Academy school in the same year, and it was built across the road from the church in 1795. Together, the two buildings formed the heart of the North Fairfield Parish. However, as the new “Weston” flourished and its population increased, there was an opposite trend in the Congregational Church’s membership. In 1830, there were only seven men and twenty-four women.

The leading cause was a revision of the Connecticut Constitution in 1818 that disestablished the Congregational Church as the state religion. This official separation of church and state created greater religious tolerance and substantially reduced congregational parish membership. Many locals left to join Methodist, Episcopalian, and Baptist churches, thriving with our country’s Second Awakening of religious revivalism.

By 1830, the original church structure was in a state of disrepair, and the remaining members voted to build a new meeting house on the same site. They selected James Johnson, son of the first pastor, to construct a new structure. He and local builder James Jennings salvaged whatever material they could, including old, notched beams that are still part of the current building. John Warner Barber’s woodcut print from 1835 gives us a sense of the planned design, and this image is the earliest recorded representation of this iconic building in the heart of our town.

When completed in 1836, the churchboasted a two-story Greek Revival façade with a decorative pediment, prominent fluted corner pilasters, and an impressive three-stage staggered steeple that surpassed the previous meeting house tower.

The Congregational Church membership rebounded after this construction phase to 102 members by 1845; this was the same year the North Fairfield Parish was established as a separate town from Weston and given the name Easton. Interestingly, when additional remodeling occurred in the spring of 1870, the original minister’s grandson, James Johnson Ward, led the redesign campaign.

Congregational Church of Easton, daguerreotype, circa 1850.

A Legacy of Yale-Trained Ministers

For much of the church’s history during the remaining 19th century, the ministers were from Yale Divinity School. Besides the first minister, Johnson, three of the church’s longest-serving leaders were Yale alumni: Nathaniel Freeman (1819-1832), Chas Prentis (1836-1851), and Martin Dudley (1851-1878). Many Yale-educated pastors stayed on as their “first call” for a few years before heading to more permanent posts elsewhere. These scholars also supplemented their income by teaching at the Staples Academy. Notable was the Reverend Edward P. Ayers (1891-1897), who lost his sight while serving the congregation. Despite this challenge, he went on to represent Easton in the state legislature and then to serve as chaplain in the Connecticut Senate.

Yale divinity students brought innovative ideas and energy to this small country parish. Ayers held musical concerts in the church to raise funds for the Staples Academy Library. Reverend Ogden (1887-1891) established a visiting lecture series for notable scholars and luminaries of the day, including Yang Phou Lee, the first Asian American to publish a book in English. A graduate of Yale, Lee condemned those who remained silent about the hate crimes against Chinese people, and he was warmly received in the Easton Congregational Church. He often returned with his wife, Elizabeth, and daughter Jennie Lee to visit.

The Reverend Herbert Hines (1914-1916) was vital for Easton’s history. He deeply appreciated the congregation’s heritage and the community’s legends and lore. He set about preserving and compiling the church’s historical records in his 1916 study, “A New England Country Parish: Its Background, History and Romance.”

Population Decline

Between the end of the Civil War and the early 20th Century, the population of Easton declined steadily. New technologies made the water-powered local mills obsolete, and new factories in large cities like Bridgeport attracted young Easton workers. The West also attracted families from the area, especially the “new Connecticut”—now Ohio, which advertised cheap, fertile land without rocks and “low taxes but still a New England way of life.” With the population of Easton declining, Church membership once again fell.

In 1922, the congregation was down to 75 church members. By then, the automobile age had arrived, and Easton began attracting commuting families to its scenic, peaceful surroundings. In 1926, Reverend Luther Stonecipher (1926-1935) became the full-time pastor. Stonecipher diligently revived the Sunday School, organizing a young person’s Christian club, the Amici Christi Society, and a Community Club for young couples. The latter would become locally famous for its monthly suppers at the Staples Academy, which had been serving as a Church Hall since 1931. Mrs. Theresa Sherwood and Mr. Eugene E. Norton purchased and donated the Old Academy building for the Church in 1937.

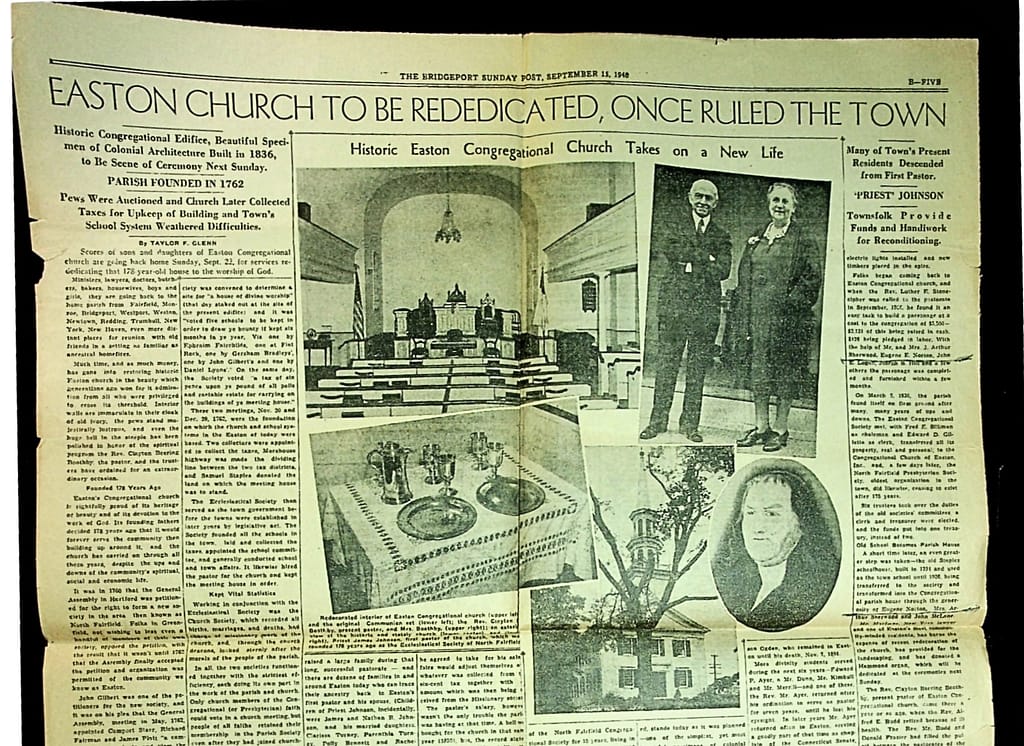

In 1940, there was another internal remodeling of the church’s sanctuary under the Reverend Clayton Boothby. Much of this work, along with surrounding upgrades to the landscaping, was funded by resident Judge John F. MacClane. MacClane, who had previously supported the construction of Easton’s Town Hall in 1937, also paid for the installation of indoor plumbing at the Academy Church Hall, a significant upgrade for the 18th-century building.

At a rededication ceremony on September 22, 1940, a new Hammond Organ played and the Reverend James F. English, superintendent of the Connecticut Conference of Congregational and Christian Churches addressed a full house of parishioners. Shortly after, Francis Mellen, a direct descendant of the original Reverend Johnson, drafted his first historical pamphlet, “A Short History of the Congregational Church of Easton.” Mellen would go on to be a founding member of the Easton Historical Society and co-authored “Easton-its History” with Helen Partridge in 1972.

Easton’s “Church on the Hill” also attracted the artistic vision of Westport resident Stevan Dohanos, a prominent American illustrator in the 1940s. He often incorporated the Congregational Church of Easton in his compositions, capturing the quintessential charm of small-town New England.

The iconic steeple that inspired Dohanos, however, was beginning to list and settle noticeably by the mid-century. In 1950, engineers with Bridgeport’s Fuller and Company inspected the structure and found substantial deterioration and weathering of timbers supporting the belfry. Their investigation showed evidence of successive preservation attempts, including numerous cross timbers, stays, and shoring to retard the spire’s northeastward movement. These findings led to the repair of several timbers on load-bearing walls, along with foundation work and the installation of steel piers to support the steeple and prevent a disastrous collapse.

Decades of Growth

Revived in numbers, the church continued to thrive, as it joined the United Church of Christ in 1957, a conference created by the union of the Congregational, Evangelical, and Reformed Churches. As a member, the Congregational Church of Easton could choose its own ministers and keep its autonomy while being part of a supportive Christian network.

With an increasing membership in 1960, church leaders expanded the original Academy building to accommodate church events. Designed by parishioner Alfred Lange of the architectural firm Lyons and Mather, the new Church Hall was dedicated with great fanfare on November 18, 1962, as part of the church’s 200th anniversary celebration. Its design honors the original Colonial simplicity of the Academy building.

The new structure’s interior reflects a mid-century modern design aesthetic with clean lines and minimal ornamentation. Its main component is a large, brightly lit central room with a wooden plank cathedral ceiling. A large kitchen with a service window adjoins the great hall for fundraising dinners and public event catering, while the lower level holds classrooms and administrative offices that would eventually become the Academy’s early educational center and the New Academy Preschool.

20th Century and Beyond

The 1970’s brought several important shifts in response to cultural and theological changes to the Easton Congregational Church. Services continued to follow a formal liturgy but now included greater lay participation. Interfaith services began with other Christian denominations in town. Notably, the Reverend Robert B. Daniels (1970-1978) started a Thanksgiving Eve prayer service in 1971 with Easton’s Jesse Lee Methodist, Christ Episcopal and Notre Dame churches. This ecumenical spirit continued into the 1980’s with the church’s “Project Concern.” This three year program celebrated the 225th anniversary of the church while extending a welcoming hand of friendship, interaction and fellowship to all members of the Easton community.

As women began playing a much larger role in all Congregational Churches, both in lay leadership and at the pulpit, Easton Congregational had its first female pastor, Reverend Allora B. Arnold, in 1985, followed by Reverends Brigitta S. Remole, Nayiri Karjian, Susanna Knox Griefen, and, most recently, Amanda Osgrove.

Easton Congregational Church has continued to catch the eye of artists, as its building has served as the setting for several film projects, including the TV drama “As the World Turns.” The church was a recurring setting for this soap opera, featuring a large-scale wedding scene in 1991 that showcased the classic white steeple and the church’s historic New England charm.

In October 2012, the Easton Congregational Church celebrated its 250th anniversary. Significant restoration was done to the sanctuary in preparation for festivities, including live music, a historical symposium, a colonial-era worship service reenactment, and a fellowship barbecue picnic.

Today, Easton Congregational Church is undergoing another renaissance, thanks to the decline in COVID cases that had affected many churches across our country. After developers offered to purchase the church land, the greater Easton community rallied to preserve this religious center and its historic buildings. A non-profit 501(c)(3) foundation was established to help restore and maintain the landmark Staples Academy building. To strengthen its sense of community, Easton Congregational has also joined a wider network of conferences, including the National Association of Congregational Churches and the Fellowship of Congregational Christian Churches of the Northeast. These organizations are opening the door to broader fellowship, spiritual growth, and shared resources for ministry.

While external affiliations may shift, Easton Congregational’s commitment to preaching the Gospel, nurturing spiritual growth, and honoring God in word and deed remains unwavering. The church is firmly rooted in its biblical foundation and historic Christian faith, continuing to uphold the authority of Scripture, the teachings of Jesus Christ, and the call to live according to God’s truth.

Even with membership ups and downs, Easton’s oldest church keeps going strong. Locals look to the building as a beacon at the very heart of Easton and by blending its historic roots with a forward-looking and Christ-centered mission, it serves today as a hub for civic dialogue and community support. Preserving the church’s landmark legacy while repurposing its spaces for community events, concerts, and educational programs is connecting its long history with the present needs of the Easton community it serves.